21 September, 2021 By: Byron Mathioudakis

The evolution of car safety has not only shaped the way vehicles appear, feel and drive today, it’s also helped dictate infrastructure, like better roads, as well as human behaviour around vehicles.

Yet safety has only achieved comparatively recent priority status in the 130-year-plus history of the automobile, having met resistance at almost every single turn.

Just how bad was it?

In the early days, such as the 1970s, most safety items in vehicles were there because of government legislation mandating it. Car companies were notoriously reluctant to give anything away for free, although today, competitive pressure often means they have to add value.

That’s why, before the 1960s, car safety was a dirty word amongst car companies, especially in prosperous Post-War America, where cars were a symbol of wealth and drove urban sprawl as living standards boomed. Cars were getting faster and flashier, but because their safety features weren’t developing at the same pace, they were also becoming more dangerous.

Looking at Australian statistics from the Department of Infrastructure, Regional Development and Cities, in 1930 there were 16.3 road fatalities for every 100,000 people, rising to 24 by 1960 before rocketing to an alltime high of 30.4 just 10 years later.

The fact that we hit a record low of 4.6 deaths per 100,000 Australians by 2018 shows the effect of vehicle safety improvements, along with accompanying road safety legislation, such as seat belts and random breath testing. But it’s been a never-ending battle.

RELATED:

What happens to your body in a crash? »

Australia's biggest safety failures

Car safety has improved dramatically over the past 60 years, but it has been a long, winding and very dangerous road to get to where we are now. Here are just some of the many car safety ‘fails’ in the intervening years.

1960 Holden FB

Australia’s best selling car in 1960, the FB featured inadequate drum brakes, primitive suspension with a habit of bouncing the car sideways, and slow and heavy non-assisted steering that required real muscle to control – often fruitlessly in an emergency situation.

It also featured vacuum-operated windscreen wipers that actually slowed down under acceleration in teeming rain.

In a crash, occupants’ heads or torsos were exposed to steering wheel spokes, protruding switches and knobs, sharp rear-view mirrors, metal dashboard finishes and windscreens that shattered.

1960 Ford XK Falcon

Designed and engineered in Detroit, the earliest Falcons suffered from catastrophic front-suspension ball-joint failure, collapsing after just a few years of hard driving over Australia’s tougher rural roads.

Another inherent danger was the steering column which jutted out in such a way as to spear the hapless driver in certain head-on collisions. Terrifying.

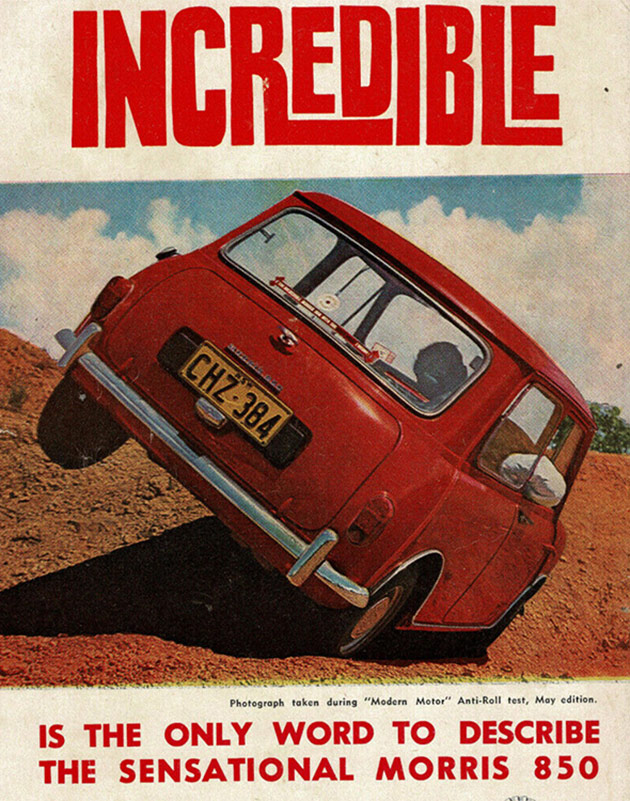

1961 Morris Mini

The original Mini’s fuel tank featured a protruding filler pipe that in certain impacts or rollovers created sparks that ignited the fuel and would incinerate the vehicle.

So dangerous was the Mini that it failed to satisfy US-market legislation and was withdrawn for sale in the USA in 1967.

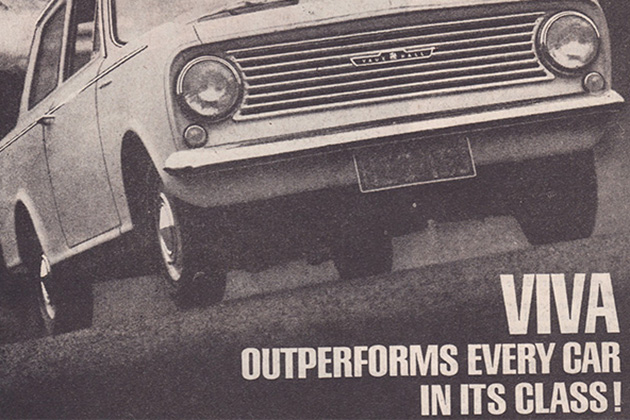

1964 Vauxhall Viva

The UK-developed but locally built HA Viva was touted as Australia’s own small car, but betrayed its ancestry by not coping well over rougher roads.

Bouncy suspension made it prone to rolling over through sharp turns. This led to a complete chassis redesign for its 1967 HB Torana successor.

1965 Holden HD

After the adored EH, Holden’s styling took a sideways turn with the long, low and wide look of the HD. But the front mudguards and their pointy shape quickly earned the unfortunate nickname of ‘kidney slicers’ due to their propensity to maim pedestrians on impact.

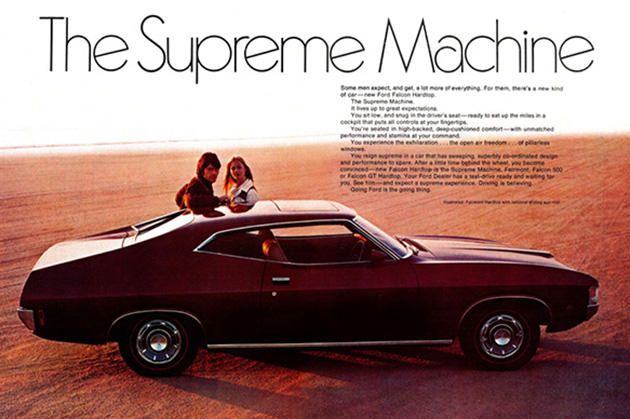

1974 Ford XA Falcon Hardtop

Following the disastrous early Falcons, Ford worked hard to ensure its big family sedan behaved like an Australian car should.

But the sleek two-door coupes of the ‘70s were impossibly difficult to see out of due to tiny side and rear windows. Low seating and a high dash didn’t help matters at all.

1973 Leyland Marina

One of the worst built and engineered cars in history, the Marina was built to replace the 1948 Morris Minor (an excellent small car in its time).

It featured antiquated suspension that struggled to keep the heavy beast stable at speed. The resulting wallow and imprecision made the Marina feel every bit the boat in choppy seas that its name implied.

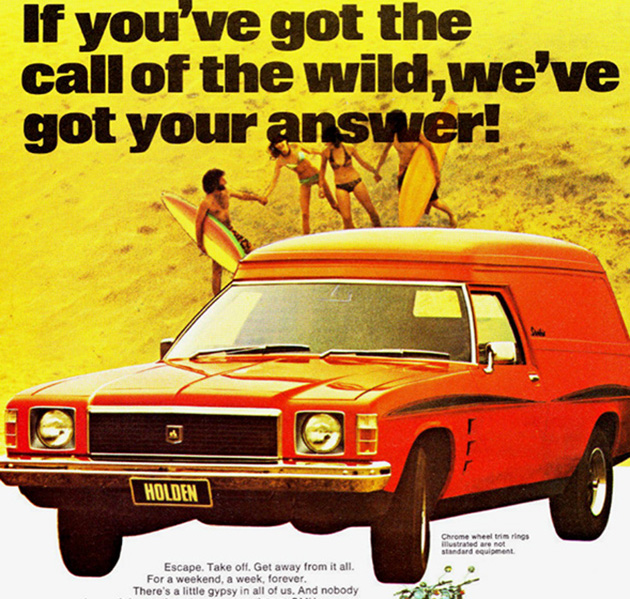

1974 Holden HJ

Excessive torque combined with insufficient brakes meant that GMH’s big family sedan of the mid-‘70s was difficult to stop safely on wet roads.

Making matters worse was overly soft suspension, inadequate tyres and a lack of basic safety features like high-beam headlight flashers. The adoption of a hard-to-read strip speedometer was a throwback too far, with critics savaging the HJ.

1988 Holden VN Commodore

The ‘big new Commodore’ featured a larger body over the older, smaller Commodore’s, but the structure did not crumple well in a crash, leading to potentially severe injuries.

Making matters worse was far too much power, that overwhelmed the rear tyres’ ability to grip. Combined with overly sensitive steering, it was dangerous in wet conditions.

1989 Ford SA Capri

The Capri’s convertible roof was great for wind-in-the-hair motoring, but the combination of a 100kW turbocharged engine in this light, front-wheel drive car with no traction control made it ‘hair-raising’ in a very different way.

The turning point

So, what changed and where are we at today?

Firstly, the world owes a debt to Swedish manufacturer Volvo, which invented today’s three-point seatbelt system in 1959 and made it available patent-free to everybody, including rival carmakers. This one act of corporate generosity is estimated to have saved more than one million lives.

Culturally, the medium of television also started playing a role in opening people’s eyes to car safety, as the nightly news beamed horror images of car crash death and destruction into loungerooms across the nation.

As the 1960s progressed into the 1970s, Australian cars gained electric wipers and padded dashboards while switchgear became recessed to avoid injury. Seatbelts gained inertia reels making them more comfortable to use and windscreens became laminated and demisters were fitted.

Child seat anchorages appeared, to promote child seats, and door latches improved to resist bursting open and ejecting occupants in a rollover. And almost all came about by law.

Further mechanical and structural changes also made cars safer as the 1980s approached. Propelling this was the advent of independent crash-test organisations like the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, today’s Euro NCAP, and later ANCAP in Australia.

RELATED:

10 safest second-hand cars under $10k »

Car bodies were designed to better absorb and dissipate crash energy, rather than transfer it dangerously into the cabin area, and fuel tanks were moved further inboard rather than hanging under the boot so they wouldn’t ignite in a rear impact.

Then, as the ‘80s wore on, electronics stepped in. Anti-lock brakes gave the driver the control to more safely swerve in a skid situation – a massive step forward.

Yet it wasn’t until US law demanded the fitment of airbags from the late ‘90s that carmakers finally turned safety into a selling point.

In 1997, the Swedes’ unique ‘moose test’ aimed at seeing how a car could avoid a moose during a high-speed swerve, exposing a flaw in the Mercedes-Benz A-Class – a small car featuring a distinctly upright design. In the test, the Benz toppled over. This led to Mercedes fitting the nascent, rollover-reducing stability control technology (ESC) as standard equipment.

Australia legislated ESC’s standardisation in the early 2010s. Today’s SUVs would be far less stable at speed without it.

Nowadays, electronic driver-assist systems include autonomous emergency braking (AEB), which automatically applies the brakes faster if the driver does not respond to the threat of a crash. Rear cross-traffic alert warns a driver of traffic and pedestrians behind the car when reversing, and in some cases automatically applies the brakes. Blind-spot monitors warn of traffic or objects that might otherwise go undetected while lane-keep assist systems help warn the driver to keep in their lane and if needed, actively steer a car to keep it within its lane.

Today, safety is right up there with affordability, design, performance and brand reputation as main motivators for buying a new car.

Legislation, along with decades of car safety development and increased consumer demand, means we are far safer in our cars than we were half a century ago. However, while car safety is generally better today, the safety credentials of modern cars can still vary tremendously, and we should never take safety for granted.

Need to check the safety rating on your next car?

Search vehicles by make and model and be sure that your next car has the right technology to keep you and your family safe on the road.