23 March, 2018 By: Vanessa Pogorelic

From weird and wonderful wind vortexes to tropical cyclones, Western Australia is home to all kinds of extreme weather events.

A s the afternoon peak hour began on a grey Monday afternoon in 2010, Perth commuters heading home were completely unprepared for what was about to unfold.

A hailstorm tore across the metropolitan area catching almost everyone unawares – everyone except the team at WA’s Bureau of Meteorology (BOM).

The thunderstorm that created the damaging hailstones wasn’t unexpected, says BOM’s Neil Bennett.

What the BOM team hadn’t seen coming that March day was the severity of the storm and, of course, the size of the hailstones.

“The intensity of that storm you don’t get very often in Perth,” says Bennett. “We usually get that kind of severe thunderstorm further to the east in the Wheatbelt.”

Forecasting and our ability to ‘see into the future’ of weather has come a long way since the first weather satellite went into orbit in the 1960s.

But weather is essentially a chaotic system so it does have a habit of throwing up surprises.

Looking into the future

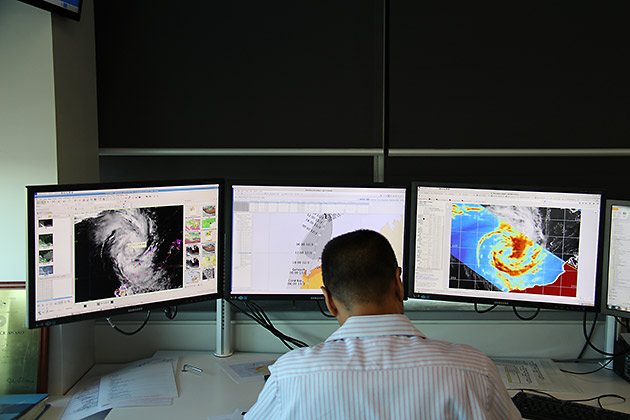

Today, the business of weather prediction involves an enormous amount of science and technology.

Bennett has been monitoring the weather for more than 40 years and says he is in awe of the way the science has advanced.

"If you’d said to me back then that we’d be able to forecast rainfall amounts and times in four days’ time for every six kilometres… well it was just not feasible then,” says Bennett.

“Today we’re using some of the most sophisticated technology that there is. We have some of the most powerful computers in Australia."

"We utilise satellites and radar and just over 90 weather stations around WA.

"At automated weather stations we can interrogate the weather data that’s collected every minute if we need to.

"We also use data from other states and other countries. There are over 200 signatories to an agreement to freely exchange this data, so it’s truly a world collaboration.”

For all the highly sophisticated technology, the perception that the forecasters often ‘get it wrong’ remains.

Bennett says the Bureau’s strike rate is actually quite high.

“On next-day forecasts we’re looking in excess of 90 per cent accuracy and our four-day forecasts are as accurate as our two-day forecasts,” he says.

“For temperature, if we’re within three degrees, we consider that a successful forecast. No one really notices the difference between 28 and 29.

“For a 100 per cent accurate forecast, you would need to measure every single element of the atmosphere across every single point on the planet.

“With the new generation of satellites, there will be more improvements though. We will be able to gather more data.

“Quantum computing also holds exciting prospects for weather forecasting because you’ll be able to crunch more data and more scenarios.

“But we will be forever chasing ourselves because as you get more accurate, people’s expectations just increase.”

Enjoying this article?

Sign up to our monthly enews

However Bennett says a world where everyone will be able to tell the weather is not that far off.

“We’re on the cusp of an absolute explosion of new technology," he says.

"In the future there will be virtual reality displays. The public will be able to interrogate the system for themselves and maybe ask, ‘I’m getting married at a certain time so what’s the likelihood of the temperature being above or below average?’

“It’s going to be mind-blowing what’s going to come out of it.”

The wind sure does blow

While hailstones can wreak havoc, typically in WA we are known for our wind - and for good reason.

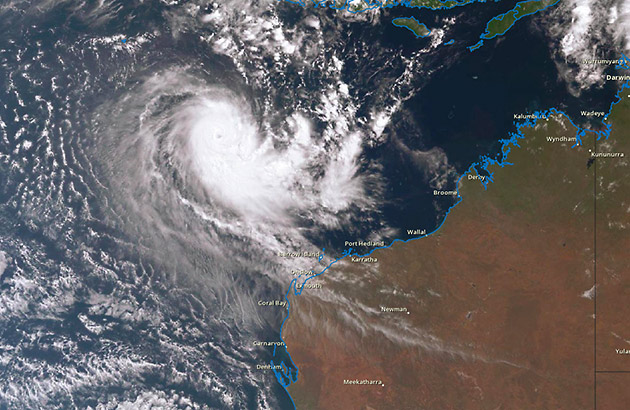

WA holds the title for the strongest wind gust ever recorded. It was 408km/h and walloped Barrow Island during tropical cyclone Olivia in 1996.

WA also experiences twisting vortex-type winds, formed by rising air which, as it changes speed or direction, creates a rotating motion.

These vortex-type winds are responsible for creating water spouts, often caught on camera by enthusiastic locals, as they skim across the ocean.

“If conditions are right, water spouts can develop when a fresh sea breeze moves in over the land,” says Bennett.

“It can even happen when there are clear blue skies.”

Water spouts have also been known to cross from water to land.

“In Perth, one came to shore a few years ago and threw some cars around," he says.

"A gentleman on a building site was picked up and thrown against a wall. The winds in them are very strong.”

The inland cousin of the water spout is the dust devil, or willy-willy. They’re formed in the same way as the water spout but with dust rotating inside.

“We get hay devils in the Wheatbelt, too,” says Bennett. “You’ll see the spinning motion because of the hay being drawn up into the air.”

Wind can also create significant temperature variations across the metropolitan area.

In summer, when the sea breeze is in, temperatures can vary as much as 10 to 15 degrees from Perth's coast in the west to the hills in the east.

During the winter months, it’s the strong cold fronts that are packing a punch.

And in spring, particularly early in the season, we can get strong winds due to the contrast between increasing inland temperatures and the cool ocean.

Fortunately, for those who like a little less motion in the air, autumn generally brings with it some relief from the windy extremes. So enjoy the calm while you can.

Stay one step ahead of bad weather

To make sure your home is ready for storm season, check our storm preparation fact sheet. It shows you some of the best ways to baton down the hatches and prepare your car and home before a storm hits.