30 July, 2018 By: Fleur Bainger

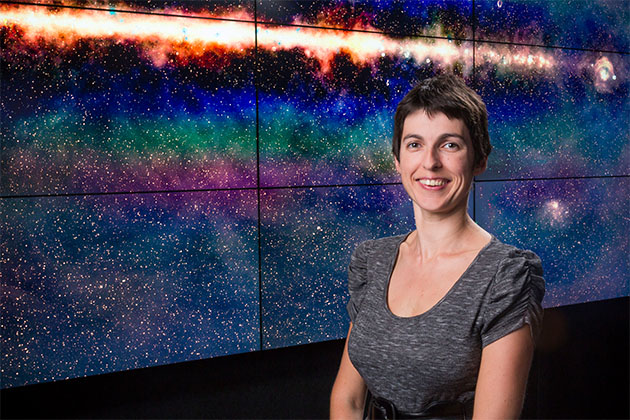

Talk to radio astronomer Dr Natasha Hurley-Walker and you’ll never look at the night sky in the same way again.

The Perth-based galaxy-hunter is using a telescope spanning nearly 6km to reveal mind-boggling details from the furthest reaches of the universe.

What’s more, she’s doing it with the help of hand-constructed antennas positioned in Western Australia’s outback, and a supercomputer based in suburban Perth.

Across the universe

So what does Dr Hurley-Walker, recently named as one of ABC's 2018 Top 5 scientists in Australia, see when she gazes at our star-sprinkled expanse?

“I’m using radio waves instead of optical light,” she says.

“What I’m seeing with radio waves is not the stars, but other galaxies. I’m looking into the deepest recesses of the universe.”

As she does, she’s able to time travel, in a sense.

“Light has a finite speed, so it takes time to reach us. The further away something is, the longer time the light has taken to reach us,” she explains.

“So as I’m looking out in the distance, I’m also looking back in time.”

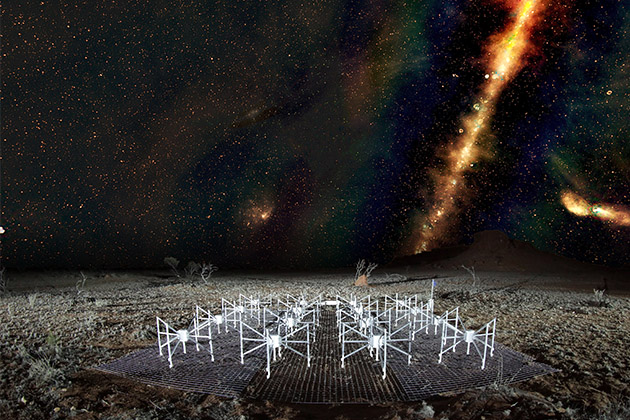

The Curtin University astrophysicist uses the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA) to enable her scientific pondering.

By detecting radio waves at low frequencies across an extra wide band, the telescope allows her to see much more, in far greater detail and significantly faster, than ever before.

“There are 128 antennas in the Murchison Widefield Array,” says Hurley-Walker.

“Most telescopes have a maximum of only about 30.”

(Photo: Radio image by Natasha Hurley-Walker (ICRAR/Curtin) and the GLEAM Team.

MWA tile and landscape by Dr John Goldsmith / Celestial Visions)

Involved in the commissioning of the MWA, she has visited the site where it spreads across the red dirt landscape of an isolated station north east of Geraldton.

“The serenity is just beautiful. Not only is it radio quiet, it’s also audibly quiet and at night it’s out of this world,” she says.

“The night skies are so dark that it’s completely utterly bright with stars.”

Discovering the stars - and Star Trek

Dr Hurley-Walker got hooked on the universe when she was just a child.

With glow-in-the-dark star stickers and correctly placed planets decorating her bedroom, she remembers being particularly struck by an episode of StarTrek – one that seems to have informed much of her adult life as a female trail blazer in her field.

The episode was when the ship’s female doctor in Next Generation gets stuck in a pocket universe and has to work out the laws of the universe in order to save her life and get back to the ship.

"She carries the entire episode herself," says Hurley-Walker.

“She works out, through logic and observation, how to save herself.

"It left a strong psychological impression.”

Hurley-Walker spent much of her childhood switching between bases in the USA, Norway and elsewhere with her oil-industry parents.

She went to high school in the UK and then to the University of Bristol to study biology and biochemistry before a persistent urge to understand the universe saw her migrate across to physics and astrophysics.

After finishing a PHD at Cambridge University, she took up a Super Science Fellowship offered by the Australian Government and relocated to Perth, joining the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research at Curtin.

While coding and deciphering data for the MWA, she rewatched all seven seasons of StarTrek. Her first child is Jean-Luc, named after the captain of the series’ ship, USS Enterprise.

Enjoying this article?

Sign up to our monthly enews

Mapping the sky

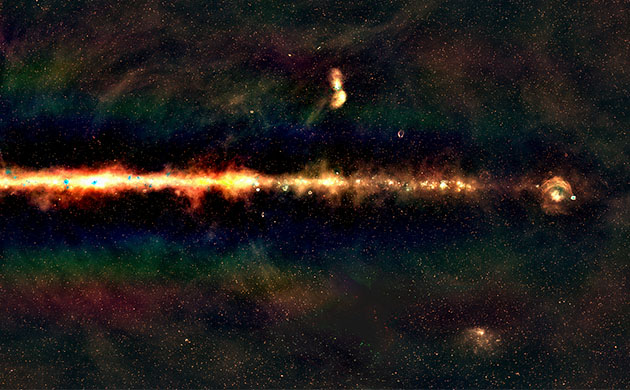

In 2016 - between her two babies - Dr Hurley-Walker released the first colour map of the entire Southern Hemisphere, called GLEAM.

The map’s creation led to Hurley-Walker being named the WA Tall Poppy Scientist of the Year for 2017.

The GaLactic and Extragalactic All-sky MWA image shows the Milky Way as an extraordinarily bright line of light shrouded in bands of red, green and blue.

The colours indicate differing radio frequencies and therefore, different ages and dynamics of the universe. It was created using colossal amounts of observational data recorded by MWA antennae.

The recordings of the data are stored in the Pawsey Supercomputing Centre in Perth. Inside a room roaring with fan noise, robotic arms pick out data tapes from a massive bank and place them in a reader for use – something Hurley-Walker says is an extraordinary sight.

“The robot arms slide along rails, and drop down like arms in an arcade game,” she says.

Seeing into the skies

Hurley-Walker says the MWA telescope, which was completed back in 2013, has been far more useful than first imagined.

“Because it’s not made of dishes, it’s just antennas on ground, our telescope can instantaneously point anywhere on the sky,” she says.

“So if another telescope discovers something interesting, for example a gravitational wave signal, our telescope can point where we hope to see the radio flare aftermath.”

The MWA was upgraded last year, doubling the telescope’s imaging resolution of the sky. Hurley-Walker now plans on doing another sky survey, hoping to produce more profound results.

“I should find about 10 to 15 times more sources, so millions of radio galaxies, many much fainter,” she says.

“Of those faint galaxies, there’s a good chance of finding some of the first to form, from less than a billion years after the beginning of the universe.”

(Photo: Dr Natasha Hurley-Walker (Curtin/ICRAR)

There are also more 'toys' coming. The MWA is a precursor to the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), a radio telescope made up of hundreds of thousands of radio antennas that will be more than 10 times more effective than what science currently uses, including the MWA.

“It will have greater sensitivity, it will have a wider bandpass and longer baselines so it’ll deliver better resolution - the list goes on,” says Hurley-Walker, who hopes to use it to see the beginning of time itself.

“I can visualise large numbers of galaxies,” says Hurley-Walker.

“But when I think that each one has hundreds of billions of stars, and each one has planets and perhaps a planet with its own atmosphere and civilisations, I get overwhelmed like anyone else.”

Photos supplied to RAC by Dr Natasha Hurley-Walker

Enjoy this story? Get more of the same delivered to your inbox. Sign up to For the Better eNews.

See the stars for yourself

RAC Parks and Resorts are within easy reach of our State's darkest skies along WA's Coral Coast and in the South West.

RAC members get up to 20%* off accommodation plus late checkout.

*Terms and conditions apply, percentage discount varies during peak and shoulder periods. Subject to availability.