11 September, 2019 By: Cristy Burne

Every two years, Australia hosts the Bridgestone World Solar Challenge, a trans-continental race of the world's most innovative solar cars. This year, a team at Curtin University is part of an Aussie push to be first across the line.

This October, more than 50 teams from 24 countries will make a 3000-kilometre journey from Darwin to Adelaide with not a drop of fuel between them as part of the 15th World Solar Challenge.

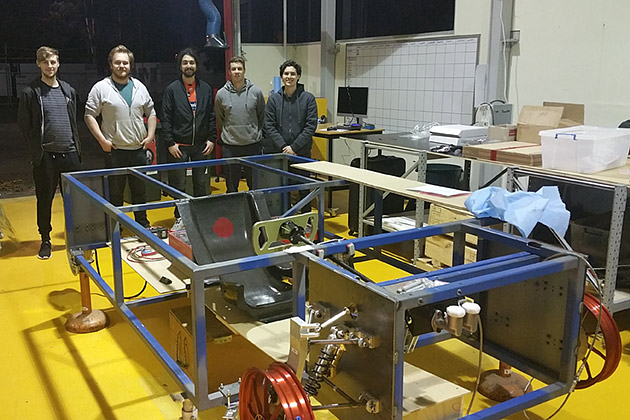

Hoping his car crosses the line first is Perth engineering student Alex Hughes, a member of the Australian Technology Network (ATN) Solar Car Team that is building a vehicle for the Challenge.

ATN is a collaboration across five states and universities: QUT, University of Technology Sydney, RMIT University, University of South Australia and WA's Curtin University.

Their aim? To create "a sustainable solar car that people will want to drive."

Making a good looking solar car

Hughes, who studies computer systems engineering and computer science, has been drawn to good-looking cars since his teens, and the one his team is building ticks all the boxes.

"It's very sleek and definitely eye-catching, a bit like a raindrop turned on its side. It's not like a car you would normally see."

The space-age look comes from balancing aerodynamics with power, then squeezing everything inside. All the solar panels are on top, all the batteries and electronics fit under the floor, and there's no need for a combustion engine. "It's actually more spacious than an ordinary car," says Hughes.

Without a fuel tank, the car will rely on its rooftop panels to absorb the sun's energy, booting electrons into motion and creating electricity. Using about enough electricity to power a toaster, it will race hundreds of kilometres a day in a bid to win in its class.

And if there's cloudy weather? No problem. The car can cover 750 kilometres on battery power alone.

"It's never going to work"

In the beginning, even the idea of crossing Australia in a solar car was considered impossible.

Back in 1982, fresh from the 1970s oil crisis, Hans Tholstrup and Larry Perkins decided to give it a go. They attempted to drive from Perth to Sydney in a homemade solar car.

“Everybody stood around and said ‘You’re mad, it’s never going to work,’” remembers Chris Selwood, Event Director for the World Solar Challenge. “As they left Cottesloe Beach, they took a bottle of seawater with them. They poured it into Sydney Harbour when they arrived.”

Though their car was called Quiet Achiever, the pair’s adventure captured global attention. The World Solar Challenge was born.

Now held biennially, the challenge attracts an international raft of students and entrepreneurs who continually push the boundaries of what is possible. Selwood calls the cars they create “mobile scientific experiments” and says innovation is what the challenge is all about.

“Our regulations are carefully crafted to state what needs to be done, without saying how it needs to be done.”

The result, he says, is the world’s most efficient electric cars, created by the world’s best and brightest engineering students.

But would you drive a solar car to work?

Cruiser class cupholders

In early challenges, winning was all about crossing the line first. Then, in 2013, Selwood introduced a game-changer: Cruiser class.

“Cruiser class is the link between purely experimental test beds and something the general public could look at and say, ‘I could drive that,’” says Selwood.

So while Challenger Class cars represent the ultimate (so far) in ultra-efficient uber-innovation, Cruiser Class cars are designed to be practical, energy-efficient and stylish.

For those who just want to be part of the fun, there’s Adventure Class in which cars could be three-wheeled, built on a shoestring or just plain different. If they meet the safety requirements, they’re welcome on the global stage.

Australia’s entry will compete in Cruiser Class, where practicality is paramount.

“We’ve even included cupholders,” says Hughes. He says driving it will feel like driving an ordinary car. “It can go up to 130km/h, but for efficiency purposes we’ll be going mid-70s.”

Enjoying this article?

Sign up to our monthly enews

Specialise and conquer

Each university has worked on a different aspect of the car’s performance: RMIT are on exterior design, UTS are tasked with interior design and mechanicals, UniSA are working on the solar array and strategy, QUT are on motor and batteries, and Curtin is focused on low-voltage electronics. For his part, Hughes designed what he calls the car’s “brain”.

“It’s the vehicle control unit,” says Hughes, who taught himself automotive electronics for the challenge. "The unit controls everything we take for granted about the way a car responds to its driver, all the driver inputs and controls, everything on your dashboard, the pedals, the lights, the indicators…”

So far, the team—and its car—is on target.

The crunch will come, Hughes says, when the five universities meet to combine their separate components into one car. “We’ll build a test rig, and if everything works nicely, we’ll be able to drive that, then move on to the final build.”

Hughes says working across Australia has been difficult, but he’s confident it’ll all come together. “We’re not just aiming to finish. We’re aiming to win.”

When it’s time to race, a roster of volunteer drivers and passengers will track the car across the desert. Behind the scenes, team members will provide advice on sunshine and weather conditions, allowing drivers to maximise their efficiency.

"You want to drive off the solar panels, but you’ve got your batteries to pick up where the solar panels can’t,” says Hughes.

The next adventure

The next adventure, says Event Director Chris Selwood, is what we as human beings do with transport technology.

Already, the Dutch team behind WSC-winning cars Stella and Stella Lux are commercialising a solar-powered family car: the Lightyear.

“Will our personal modes of transport be like the cars we drive today, but with a different engine?” Selwood asks. “Maybe, maybe not. It’s about broad thinking, different solutions, and different ways of thinking about different problems.”

You can follow the race at worldsolarchallenge.org

Image credit: Bridgestone World Solar Challenge

We're working towards the future, too

An important part of our planning for the future is looking at how we can live, work and move around our State more sustainably.